By Karen Price

Traditional grantmaking in community-based projects usually involves clearly defined timelines, benchmarks and outcomes.

Setbacks aren’t often viewed as opportunities.

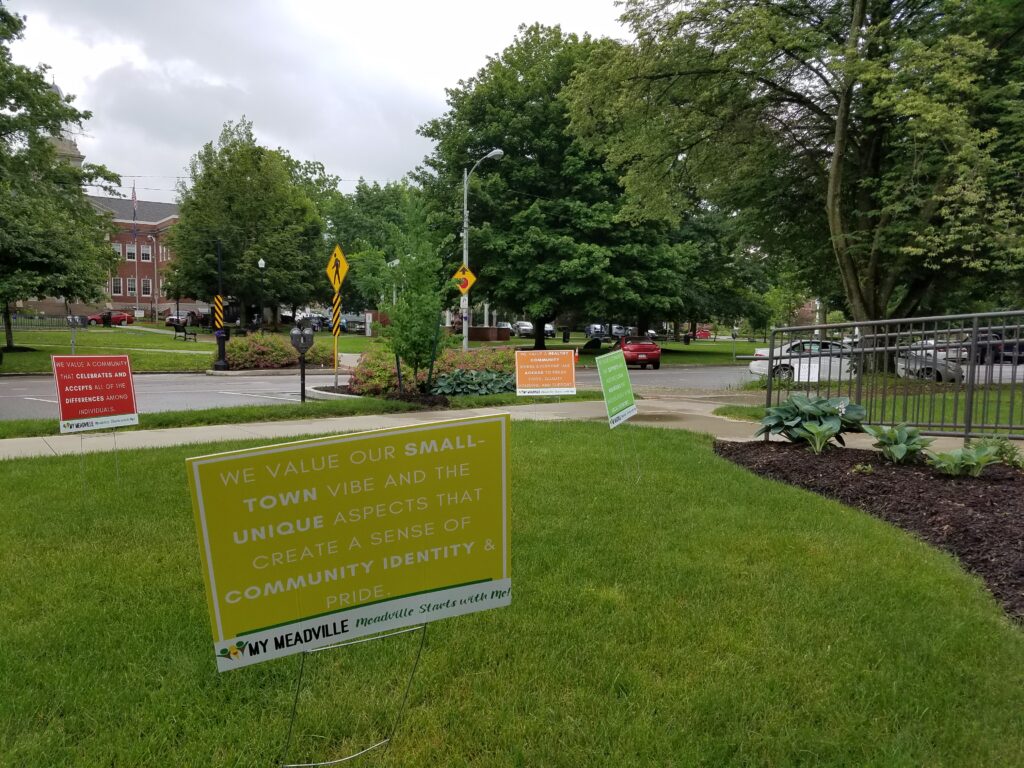

But with emergent strategy, both funders and grantees are encouraged to be open to change while still having goals and objectives. Operating outside of a compliance mindset isn’t always easy for funders or grantees, but being in the moment and creating the space for building relationships and conversations – to ask questions, get creative and not be afraid to fail – leads to greater curiosity, imagination, and, ultimately, the potential to change what we see around us and create a more equitable future. That was one of the lessons revealed in Elizabeth Myrick and Rachel Mosher-Williams’ research into PA Humanities’ PA Heart & Soul initiative in the three pilot communities of Meadville, Carlisle and Williamsport.

“Failure is learning, and learning is growing,” PA Humanities senior director of content and engagement Dawn Frisby Byers said. “I am not sure if any new project, or, frankly, any person can really grow without failure. Even in your personal life, the things that you fail at are the things that you’ve learned from. It’s rare to have an organization that has that mindset at the beginning, that we’re walking into a new territory and we’re not quite sure what we’ll find, and we may stumble along the way. We begin each project, whether it’s PA Heart & Soul, or any of our other programs, with an idea, but not necessarily a prescribed method of doing so. When we work with community, we really want to advance the work, but we’re so very, very interested in the contributions and working with the community to create this path, and no project is the same.”

This is the second part of a two-part look into emergent learning and strategy, and research into the PA Heart & Soul project. Click here for part one.

All three of the pilot communities experienced power dynamics, politics, the involvement of fiscal sponsors, and the ability of the humanities to help communities heal and account for different narratives and acknowledge harm. Exactly how that all played out, however, was different in all three.

“I really do think this process made us rethink the way we work with our grantees,” PA Humanities senior program officer Jen Danifo said. “Something I’ll take away is that it really helped us understand the context of where people are living. You can apply to do programs that sometimes go well as exhibits contained within walls, and maybe it’s easier to do that, but going into the community and doing engagement with the humanities is very complicated and it’s going to look very different than a museum program. That was a huge learning for us.”

Among the lessons learned from the research is that setbacks in and resistance to the power-sharing aspects of Heart & Soul implementation are inevitable, and that pursuing equity explicitly and transparently is essential when faced with setback and resistance. They found in doing the research, Myrick said, that it could be difficult for team members to not give rose-colored glasses answers to how things were going at times because PA Humanities was the funder.

“We found that they reflected on the fact that they felt that way when we into the learning project,” Myrick said. “Coming from the outside, folks felt safe in sharing what really happened, what was hard, what was really great, the challenges they faced, and just having a little wiggle room between the funder and the grantee allowed some of that truth to come out. And that’s what’s exciting, is (PA Humanities) is now building into their processes and reinforcing that safe space for the next communities.”

Releasing everyone from the compliance mindset, Mosher-Williams said, requires practice. She likens it to learning to play an instrument.

“You’re practicing paying attention, you’re practicing listening, you’re practicing hearing other stories, and you’re practicing being in relationship,” she said. “One of the threads that goes through all these things is that connections and relationships themselves are a measure of progress. Those things are incredibly important, and make all of this work and make our communities work.”

The word that comes to Frisby Byers’ mind when she thinks of letting go of the compliance mindset is “fluid.” There has to be the understanding that every town in PA Heart & Soul moves at a different pace.

”You have to come in and be present and have the conversations with and around what’s going on,” she said. “Our team regularly checks in with whomever we’re working with just to make sure there’s progress, not by prescription but just as opposed to being stuck. Because this work is not just new to us. It’s a different way of working for everyone.”

![[color – dark bg] PA SHARP FINAL FILES DB 72dpi [color - dark bg] PA SHARP FINAL FILES DB 72dpi](https://pahumanities.org/uploads/files/elementor/thumbs/color-dark-bg-PA-SHARP-FINAL-FILES-DB-72dpi-phgl7aimtfdpzt2rscvl43ksfv3asbbls19lsvuacw.jpg)