By Karen Price

When young people tour the Paul Robeson House & Museum in West Philadelphia, Janice Sykes-Ross likes to ask them a question: Who’s the most famous person you can think of, dead or alive?

Michael Jackson is a popular answer. So is Beyonce.

Paul Robeson, Sykes-Ross tells them, was even more famous in his day.

“But I don’t think there’s any one person I can say compares to Robeson, because he was so many different things,” said Sykes-Ross, executive director of the museum.

The West Philadelphia Cultural Alliance and Paul Robeson House & Museum, which received a PA SHARP – Sustaining the Humanities through the American Rescue Plan – operations grant to aid in pandemic recovery and growth, works to share the legacy of the multi-faceted entertainer and political activist. This April, they’re celebrating his 125th birthday and will use the occasion to further spread the word about who he was and the causes for which he stood.

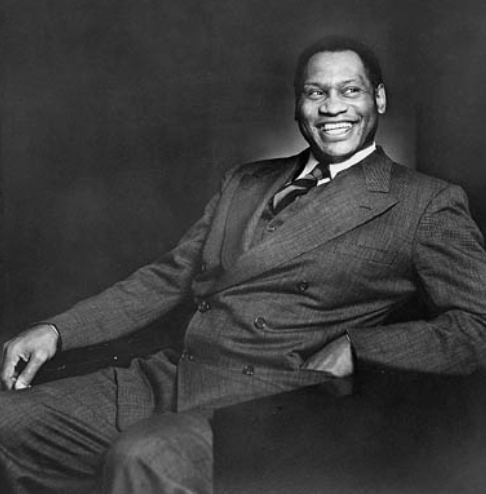

Robeson, the son of an enslaved man who escaped to freedom, became just the third African American to attend Rutgers University, where he was a five-sport college athlete and a member of the prestigious Phi Betta Kappa and Cap and Skull academic honor societies. He then graduated from Columbia law school before becoming one of the most famous entertainers in the world in the 1920s and 30s. He performed everything from Shakespeare to musicals on Broadway and London’s West End – his rich, bass-baritone voice defining songs including “Ol’ Man River” from Showboat – and made more than a dozen Hollywood films.

Yet despite his global fame and success, racism was ever-present in Robeson’s life. He spent most of the 1930s living in London, traveling and becoming familiar with the struggles of oppressed people throughout the world. He became an activist, using his platform to speak out against racism, Jim Crow laws and injustice in the U.S. and abroad.

He also suffered the consequences.

Robeson was closely allied with the Soviet Union and its people, once saying that there he felt like a human being, walking in full human dignity, for the first time in his life. In the era of McCarthy and the Cold War, not everyone in the U.S. appreciated the sentiment or his refusal to distance himself from the Soviets or disavow communism. After Robeson’s speech at the Paris Peace Congress in 1949 was misquoted back in the United States to say that Black Americans would not fight against the Soviet Union, he was vilified and labeled a traitor. His reputation plummeted, the government revoked his passport in 1950 and some leaders of the burgeoning Civil Rights movement, including the NAACP and Jackie Robinson, distanced themselves from him.

“The world was listening; he had a world stage to speak,” Sykes-Ross said. “So that in itself is pretty terrifying to the powers that be, especially if they can’t get him to align the way they want him to align with them. You’re OK as long as you’re singing and bringing joy and speaking complimentary things, but the minute he starts to take on what is presumed as a radical approach to what’s going on in the country and the world, it’s like, ‘Whoa, we have to silence this. We have to find a way to not only discourage people from aligning with him but also find a way to start discrediting him.’”

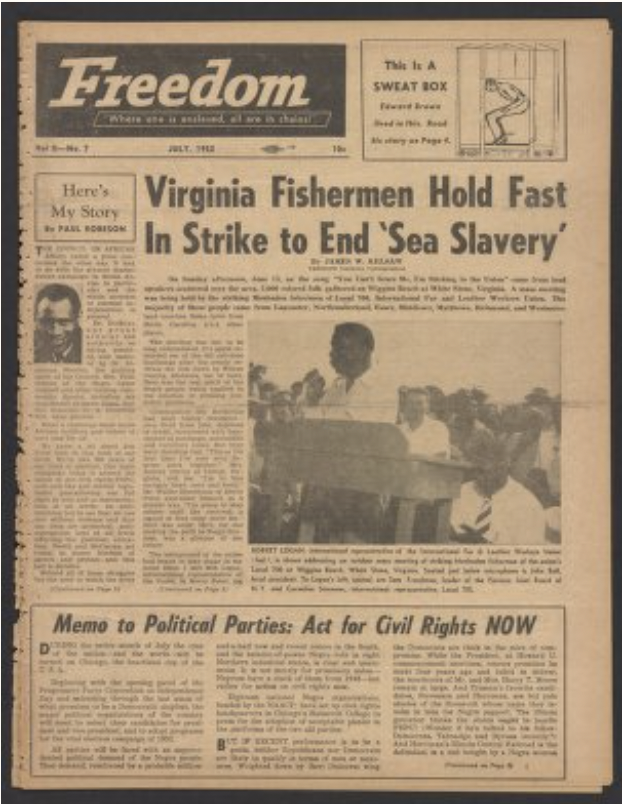

Robeson could no longer travel abroad, and he was persona non grata at home. Concerts were canceled, his albums were pulled from shelves and acting roles dried up. His income fell to almost nothing. Still, Robeson found ways to stay connected, including publishing the Freedom newspaper with fellow activist Louis Burnham to challenge racism and oppression worldwide and advocate for civil and labor rights beginning in 1950. He also performed concerts over the phone and even once from a flatbed truck at the Canadian border.

“At one point he’s simultaneously winning awards for notable and distinguished service in human and labor relations, and being investigated by the FBI as a communist,” Sykes-Ross said. “And yet even after all this he continues to perform, he continues to stand up for what he believes is right.”

The turmoil took its toll, however, and Robeson’s health suffered. He became a recluse after his wife passed and he moved in with his sister in the West Philadelphia house that is now the museum. He died in 1976, still under FBI surveillance as he had been since 1941.

The home sat empty for 12 years until the West Philadelphia Cultural Alliance purchased it in 1994 and began restoration. The museum currently houses memorabilia from his life, including albums, paintings, books and photos, and serves as a gathering place for community programs.

As part of the 125th birthday celebration being held April 8-15, they’re joining with other houses and centers dedicated to honoring Robeson’s life including the Paul Robeson House in Princeton, New Jersey, where he was born. The premier event in Philadelphia will be held at the Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts at the University of Pennsylvania and includes a performance by Sweet Honey in the Rock and a keynote address by Gina Belafonte, daughter of Harry Belafonte and CEO of Sankofa.org. Harry Belafonte, who was a mentee of Robeson, and Danny Glover are honorary chairs.

For more information on all the celebratory events and trips planned, click here.

Vignettes of Robeson’s life were featured on the organization’s website and social media throughout Black History Month, and other initiatives include plans to have the street in front of the house at 50th and Walnut renamed Paul Robeson Way and to increase his name recognition and place in history as one of the first to use his platform as a world-renowned artist as a tool to fight social injustice and bring about change.

“No matter how much money they took from him or how much they did to hurt his health, that’s something that still stands to this day,” said Chris Rogers, program director at Paul Robeson House. “People have critiques about certain choices he made, but he has an unblemished record of artistic integrity, of saying, ‘I choose to fight for freedom. And I took the punches.’”

![[color – dark bg] PA SHARP FINAL FILES DB 72dpi [color - dark bg] PA SHARP FINAL FILES DB 72dpi](https://pahumanities.org/uploads/files/elementor/thumbs/color-dark-bg-PA-SHARP-FINAL-FILES-DB-72dpi-phgl7aimtfdpzt2rscvl43ksfv3asbbls19lsvuacw.jpg)