Leadership at the one-time home of steel magnate Henry Clay Frick is working to show a broader picture of the city during the Gilded Age and the time period’s impact on the modern era.

By Karen Price

In Pittsburgh, The Frick’s Clayton house is a window into the Gilded Age, a 23-room mansion located in the area once called Millionaire’s Row because of the titans of industry who lived there.

It was the home of Henry Clay Frick, who made his fortune supplying fuel material for iron and steel manufacturing, and since it opened as a museum in 1990, visitors have gotten to see what a day in the life was like for the family and the people who worked there. But as the 30th anniversary approached, leadership of The Frick Pittsburgh wanted to reexamine the stories they tell and the history they share. The events of 2020 only reinforced that desire, and a reinterpretation project is now underway supported in part by funding from a PA SHARP – Sustaining the Humanities through the American Rescue Plan – grant from PA Humanities.

“We wanted to think about the fact that the Fricks lived in a really important time in our history,” said Kelsie Paul, manager of interpretation and engagement at The Frick Pittsburgh. “We thought we were doing a good job of explaining how the Fricks lived, but what if we zoomed out a little bit and put them more in context rather than just their perspective as a white, wealthy family living in an upper class neighborhood? What would it look like if we talked about life in Pittsburgh as a whole?”

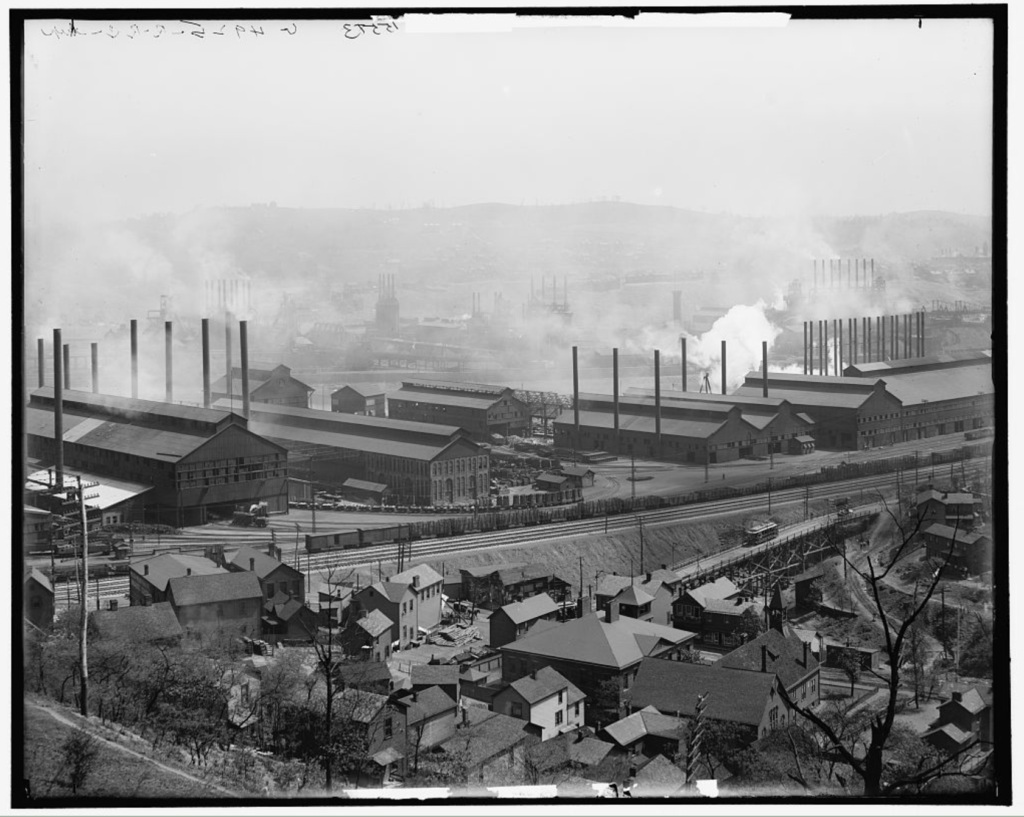

Frick’s is the tale of an immigrant farmer’s child who helped make Pittsburgh the steel capital of the world and grew wildly wealthy in the process. It’s also the story of a magnate who was staunchly against organized labor in an industry known for grueling work in dangerous conditions. His decision to call in the Pinkerton Detective Agency to the Carnegie Steel Company’s mill during the Homestead Strike of 1892 led to a gun battle that left nearly a dozen dead. At Frick’s request, the National Guard came and took control of the mill and the town, the union collapsed, and according to historians, worker wages plummeted while shifts rose from eight to 12 hours.

Now, only a few token remnants of the mill remain among the chain stores and restaurants that make up The Waterfront shopping center in Homestead. But just three miles up the Monongahela River sits U.S. Steel’s massive Edgar Thomson Works, and to this day not everyone in Pittsburgh thinks highly of Frick.

“We recognize that Mr. Frick has a pretty fraught legacy in Pittsburgh, depending on who you’re talking with, and people may have strong feelings about him and the things he did, particularly in relation to the labor movement,” Paul said. “We’re really at the beginning of the reinterpretation project and exploring things we can do in unpacking that and exploring that further.”

Another intention of the reinterpretation is to explore how the decisions and events of the Gilded Age helped create the country we live in now, Paul said, and the similarities between current events and that period in history. That includes the gap between the wealthy and the poor, major technological advancements, immigration and other issues.

As the events of 2020 unfolded, particularly nationwide demonstrations calling for racial justice in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, it prompted even greater reflection of The Frick Pittsburgh’s place in the community.

The house and accompanying art museum, car and carriage museum, cafe, gardens and greenhouse are located in the upper middle class, predominantly white neighborhood of Point Breeze. Across Penn Avenue is Homewood, a predominantly African American neighborhood that became one of the city’s poorest and most racially segregated during the latter part of the 20th century. Black Lives Matter demonstrators on several occasions marched through Point Breeze to the home of Pittsburgh’s mayor at the time, less than a mile from The Frick.

Internally, Paul said, they’d had many conversations about the perception of The Frick as being an elite institution. As an organization, the events of 2020 strengthened their commitment to consulting with their community and leaders in equity work in the museum field to build more relevant, inclusive programming and interpretation.

For instance, she said, not everyone is interested in or feels connected to the traditional European art that was part of Helen Clay Frick’s collection and now makes up a large part of the art museum. This past summer, the special exhibit “Slay” placed 17th-century Italian painter Artemesia Gentileschi’s painting of Judith and Holofernes next to a version by contemporary Black artist Kehinde Wiley, known for recontextualizing old master works. The exhibit was meant to inspire “an exploration of violence, inequality, oppression, and identity, as well as the portrayal of women—particularly women of color—in art history.”

While the Clayton reinterpretation project is still a work in progress, Paul said, they want to ensure that The Frick Pittsburgh is a place for everyone.

“Really, that’s the long goal and we’re working to find a way that Clayton fits into that,” she said. “I know a museum house can feel off-putting or unrelatable to people, but we’re hoping to change that experience and break that down. We want to find a way to open our doors and more widely serve the whole community. That’s important to us.”

![[color – dark bg] PA SHARP FINAL FILES DB 72dpi [color - dark bg] PA SHARP FINAL FILES DB 72dpi](https://pahumanities.org/uploads/files/elementor/thumbs/color-dark-bg-PA-SHARP-FINAL-FILES-DB-72dpi-phgl7aimtfdpzt2rscvl43ksfv3asbbls19lsvuacw.jpg)