Assemble and Philadelphia’s Brandywine Workshop and Archives are both using PA SHARP funds to bring more diversity into schools.

By Karen Price

The contributions of African Americans are everywhere, but so often missing from the lessons taught to children about history makers and ground-breaking leaders in science, technology, engineering, art and math.

Take for instance driving a vehicle. Many people would be surprised, Ja’Sonta Roberts said, to learn that African American mathematician Gladys West helped develop the GPS system that we use to help us get from place to place. Or that the inventor who patented the yellow light as a much-needed warning between green and red in traffic signals was an African American man named Garrett Morgan.

Roberts and her colleagues at Assemble, a youth-oriented, maker-focused nonprofit in Pittsburgh, aim to change that with the Afrofuturism curriculum they developed with the help of funds from their PA SHARP grant from PA Humanities.

“Hopefully one day we won’t need something that’s separate, that these accomplishments will always be represented in every walk of life and so it won’t be necessary,” said Roberts, the off-site programs manager at Assemble. “But until we can get to that day, we’ve got to continue to fight to make sure that these folks have light shined on everything they’ve provided us over the years.”

Assemble is one of three PA SHARP grantees that are bringing diverse voices into the educational space. Last month we spotlighted Philadelphia’s Nueva Esperanza, which is using its grant to create a series of educational videos and accompanying curriculum spotlighting Latino leaders in the arts. We now look at Assemble’s efforts to teach students about leaders from the African diaspora in STEAM fields as well as a database project from Philadelphia’s Brandywine Workshop and Archives called Artura that makes diverse, contemporary artists more accessible.

At Assemble, a community space for arts and technology located in the Garfield neighborhood of Pittsburgh, organizational leaders first tested a pilot of the Afrofuturism curriculum in an after-school program at Westinghouse High School in 2019. They started with five students. By the time they had to shut down because of COVID-19, they had 25 students who’d mostly learned about it through word of mouth.

“It was like all the lightbulbs went off and confetti fell,” Roberts said. “This was working. Kids have a voice and they want to be able to express that and see folks who look like them doing these things. They want to see that this is a space for them as well.”

They’ve since created a curriculum for kids from kindergarten through high school, some with accompanying zines. A number of schools in the Pittsburgh region have started using their materials, and they’ve also used the curriculum in their own summer camps, special programs and partnerships throughout the city. Every lesson is heavy in maker activities, but they also include history and discussion about the struggle to be recognized and the importance of building equitable communities.

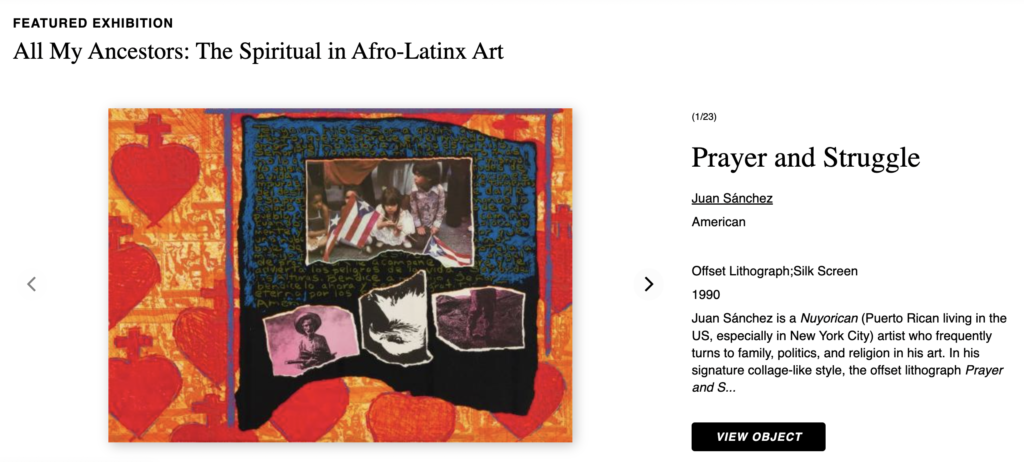

The project at Brandywine, a diversity-driven nonprofit located in Philadelphia, also grew from a desire to shine a light on individuals whose contributions to their field are overlooked and at risk of being forgotten. In their case, that means art and artists. While there was an explosion of creativity following World War II, both textbooks and museums often reflect a very narrow sliver of that work.

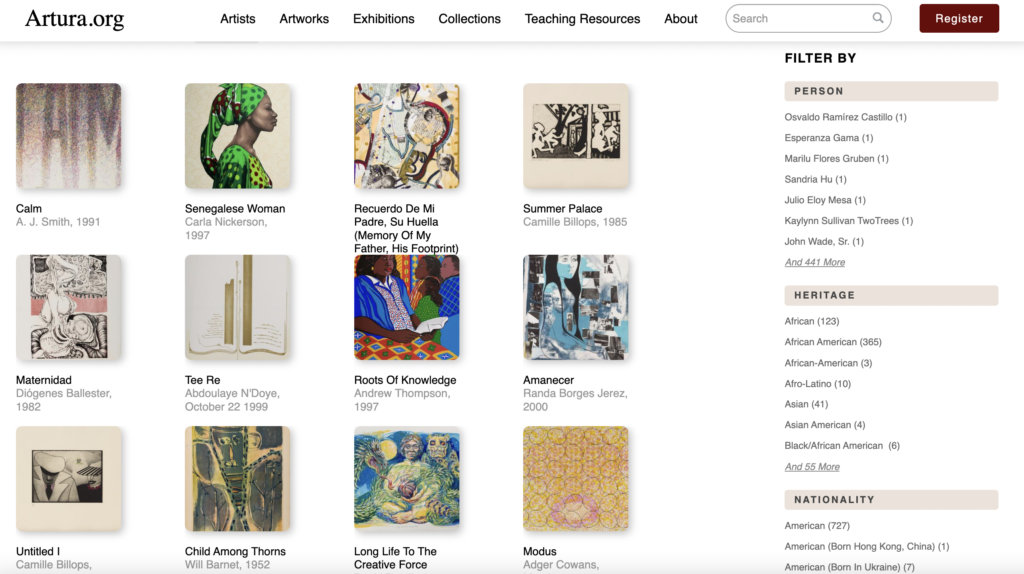

“We asked the question, ‘What if there was an online database, the equivalent of Artstor or IMDB, that could be this de facto, go-to database for all this art that was basically unaccounted for,’ and what if it was specifically inclusion-oriented?” said John Cardone, the founder and principal of Being Design who developed Artura.org. “And how might we help the education system more accurately reflect the reality of our culture? The only way is to do the work of making a single resource everyone can go to where all the otherwise neglected production is now archived, collected, searchable, filterable, shareable, browseable.”

The database, which is free to access, includes over 1,400 images of diverse contemporary artwork, 650 biographies of artists and 60 lesson plans exploring the heritage and personal experiences of the artists. Among the heritages well-represented are African-American, African, African diaspora, Asian-American, Asian, Asian Diaspora, Latin-American, South and Central American and Native American. There are two teacher guides as well as resources for teaching about the slave trade, for example, or the Holocaust.

“The idea is definitely to be a resource for teachers, but not just art teachers,” said Matt Singer, director for administration and development. “The idea of incorporating non-white, non-western people and voices and narratives into the existing U.S. educational curriculum definitely extends beyond the sphere of art. It should be reflected in the study of language, literature, history, math and science. There’s also been an effort to connect works with poetry and song. It’s all mutually reinforcing and helping different kinds of teachers incorporate diverse voices and find new materials to teach with.”

They are currently working toward spreading news of the database across the state, especially among educators in the arts and humanities. They also hope to continue to expand the database and document the work of diverse artists from WWII until 2012, when the internet made the works more widely available and accessible.

Assemble also hopes to expand the reach of the Afrofuturism curriculum by getting it fully licensed. The project hasn’t been without its challenges, including from those who question why it’s relevant to students who aren’t of color.

“And it’s because these people contributed to these fields and they’ve not been given a voice,” Roberts said. “We’ve not been able to see their contributions that we use in our everyday lives, the inventions and innovations and pathways created by people of color. If we want to educate and talk about STEAM and be equitable, then we have to start with making sure we’re allowing those who are folks of color to have that voice in what we do.”

![[color – dark bg] PA SHARP FINAL FILES DB 72dpi [color - dark bg] PA SHARP FINAL FILES DB 72dpi](https://pahumanities.org/uploads/files/elementor/thumbs/color-dark-bg-PA-SHARP-FINAL-FILES-DB-72dpi-phgl7aimtfdpzt2rscvl43ksfv3asbbls19lsvuacw.jpg)