Archives help to preserve history, and in the case of the LGBTQ+ community archives can reveal lives and histories that for too long remained hidden or underground.

Two organizations on opposite sides of Pennsylvania are currently using their collections to preserve and share the stories of the LGBTQ+ community using funds provided by PA Humanities through the PA SHARP — Sustaining the Humanities Through the American Rescue Plan — grant program.

The Mattress Factory contemporary art museum in Pittsburgh recently held a “Queer Afterlives in Artist Archives Symposium” and a celebration to launch the release of extensive public archives documenting the life and work of genderqueer artist Greer Lankton. In Allentown, the Bradbury-Sullivan LGBT Center is building a community archive documenting the rich history of local and regional LGBTQ+ life and activism including print material, signs, memorabilia, garments and oral histories.

“Often times we learn about history at a very large level so being able to have access to that local history gives people a sense of belonging to the place that they live in, which is so important,” said Robin Gow, cultural and community programs manager at the center. “You’re able to know that people have been doing things here that were unique and different and special and specifically attuned to this landscape.”

The archival exhibit currently featured at the center is called “Pride in Print: Moving Above Ground and Embracing our Gaydar.” It showcases two different local print magazines, and the reception for the opening brought together multiple generations of community members.

“I think the archive is really doing that work creating intergenerational conversations and understanding of the fact that LGBT people didn’t just exist in New York and San Francisco,” Gow said. “These groups of people have been organizing and using their own strategies and tactics for organizing in regional areas, too, and I think it helps queer people in the area feel a deeper connection to understanding that queer people existed everywhere. Being able to see that in archival material is really valuable in that way.”

At the Mattress Factory, the Greer Lankton archives are helping to bring greater recognition to and understanding of the artist. Best known for creating life-sized dolls from papier mache and other materials, Lankton lived in the East Village of New York City in the 1980s and her autobiographical pieces frequently explored and questioned themes of gender and sexuality norms.

“She’s always been overlooked a little bit,” Mattress Factory digitization archivist Sinead Bligh said. “She’s always been seen as Nan Goldin’s muse and David Wojnarowicz’s muse and Peter Hujar’s muse, but she was a subcultural icon in her own right.”

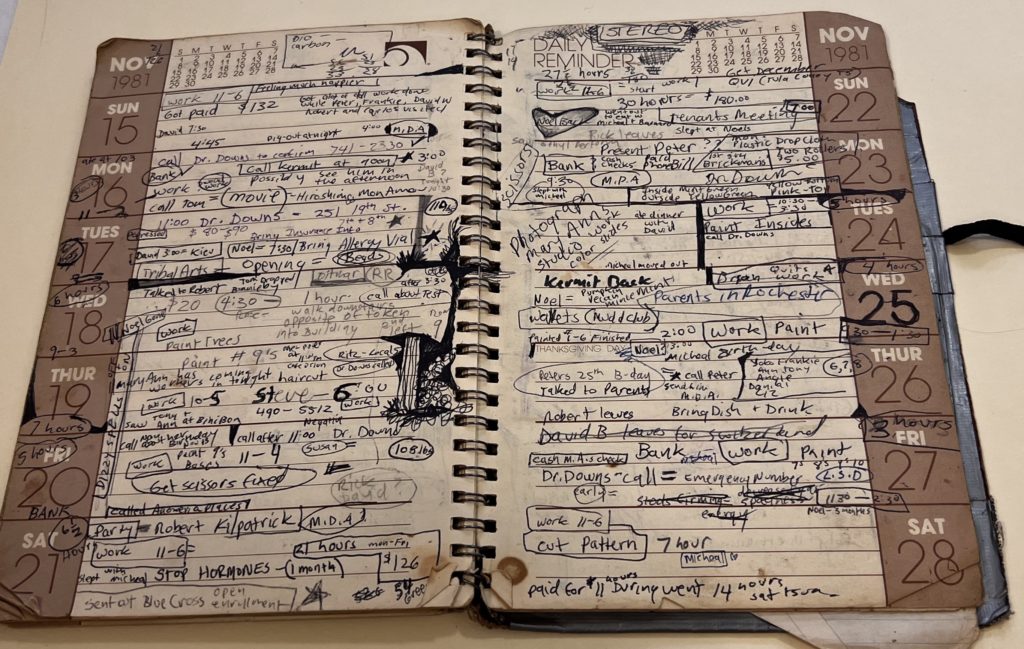

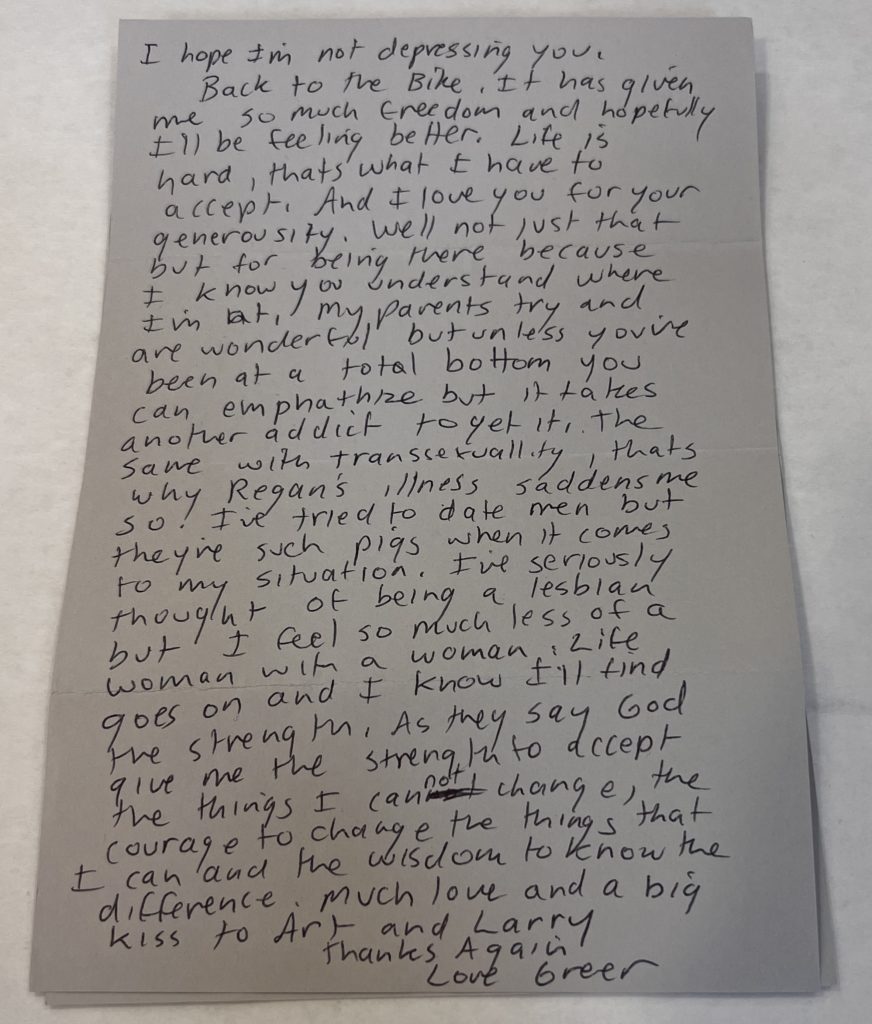

Archivists worked over the last two years to digitize and describe over 15,000 items donated by the Lankton family, including family photographs, letters and day planners in addition to drawings, paintings and sketchbooks. Those items are now available online through the Mattress Factory website.

“One thing that was surprising I think was her attention to detail in capturing her life and really archiving her life,” Mattress Factory senior archivist Sarah Hallett said. “It’s pretty rare to find, I think, in artist archives. She had really just documented every aspect of her life, so that was really exciting.”

The collection offers insight not only into Lankton’s works but also her sexual and domestic abuse, gender transition, struggles with addiction and an eating disorder and life in New York City during the peak of the AIDS crisis.

“Her resilience, I think, is what comes through for me,” Bligh said. “She was an incredibly resilient person.”

Lankton said her work was “all about her,” reflecting her life as an artist, as a transgender person and her substance use and addiction. The symposium brought together archivists and scholars with artists whose work engages with archives, the histories of queer art and the identities it can reveal. The archives themselves offer an unfiltered and fascinating look into the life of Lankton, who passed away in 1996.

“I think there are a lot of different narratives out there about her and her life and her story and so I think to have this collection and be able to preserve it, organize it, and digitize it lets her take control of her own narrative and put out there the things that she kept,” Hallett said. “I think it’s really important, and we’re very proud.”

![[color – dark bg] PA SHARP FINAL FILES DB 72dpi [color - dark bg] PA SHARP FINAL FILES DB 72dpi](https://pahumanities.org/uploads/files/elementor/thumbs/color-dark-bg-PA-SHARP-FINAL-FILES-DB-72dpi-phgl7aimtfdpzt2rscvl43ksfv3asbbls19lsvuacw.jpg)