For author Alex London, dystopias are not just a fun premise for a novel. In a recent visit to the teens of Huntingdon Valley Library’s Teen Reading Lounge program, London emphasized the extent to which dystopias should reflect and engage with real-world issues in a meaningful way. When he was 21, London had the opportunity to work with Refugees International, an organization which advocates for the rights of displaced people around the world. He wrote a “grown-up book” based on this experience, One Day The Soldiers Came, in which he interviewed children in war-torn areas. This gave him an interest in how children and teenagers are able to adapt to adverse circumstances, which over time gave him the impetus to begin writing science-fiction novels, the first of which was Proxy.

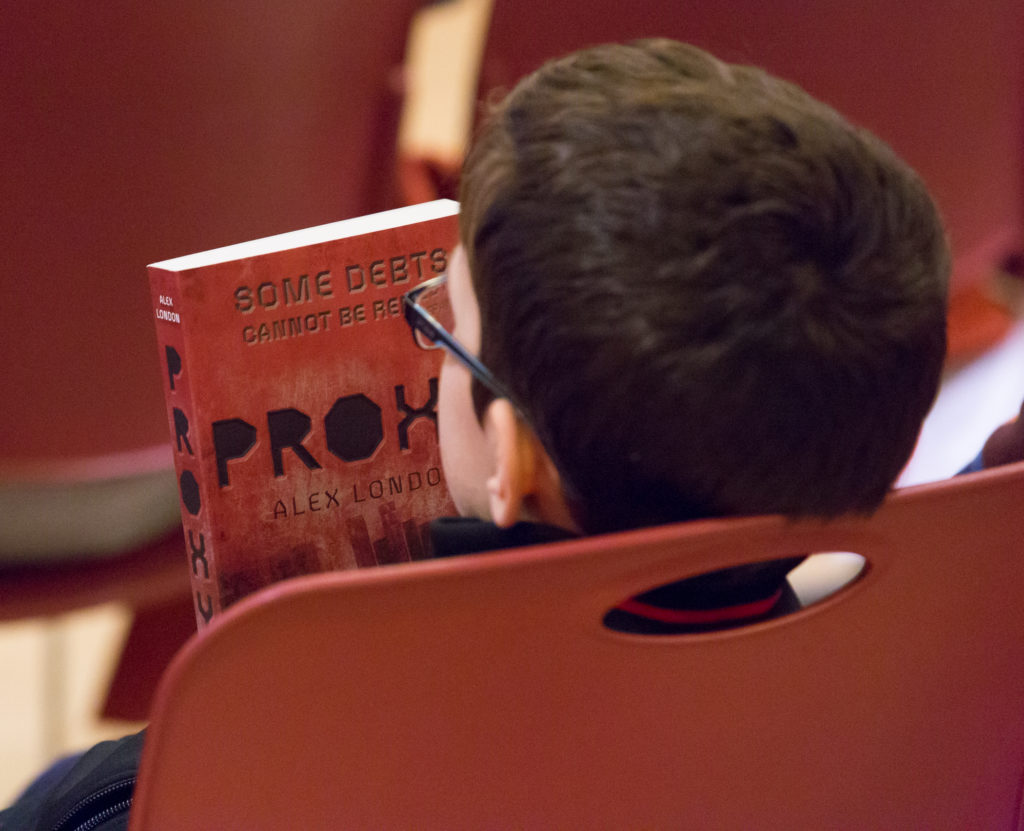

When a teen asked about his inspiration for writing Proxy, London said that he wrote the book that he needed when he was a teenager. Citing his love of Orson Scott Card’s Ender’s Game while decrying the blatant homophobia espoused by the author himself, London set out to write a dystopian novel that engaged with societal problems through the eyes of a protagonist who is openly gay while not being solely defined by his sexuality. Proxy is set in a rigidly structured society in which the poor are constantly indebted and are forced to serve as proxies to the wealthy elite, taking punishment for their transgressions. The novel examines many issues, including class, consumerism, and climate change, and in his talk London discussed the importance of these issues by connecting the fictional dystopia to aspects of the real world.

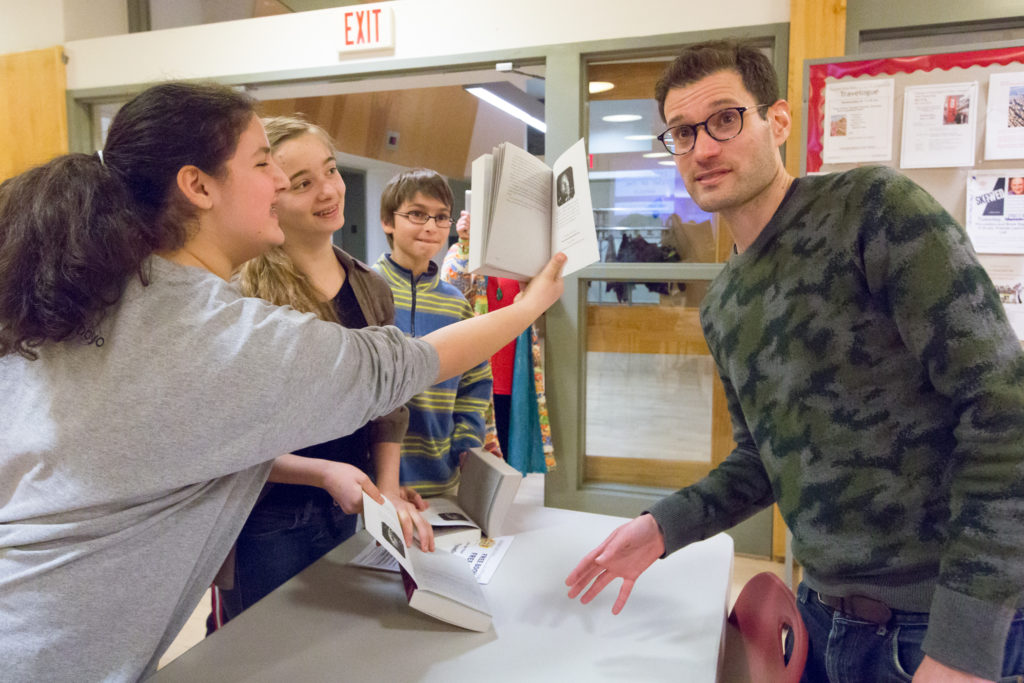

The teens at Huntingdon Valley were enthralled by London’s charismatic presentation, and they never ran out of questions to ask. We at PHC did have the opportunity to ask more questions, and we were interested in what London had to say more broadly about the importance of literature and the humanities in the lives of teenagers.

What motivated you to join and work with Refugees International in the first place?

I wish I could say it was some noble drive; but I was 21 and really craved adventure. I was also terribly curious how, in the early days of the 21st century, wars were being fought by, for, and around children all over the world and no one was paying much attention to what they thought about it all. My curiosity got the better of me and I raised some funds, partnered with the amazing people at Refugees International, a refugee advocacy organization, and began traveling to learn about the lives and perspectives of young people affected by armed conflict. They very quickly showed me that they were the protagonists of their own lives with stories as epic as anything in literature. I knew I had to do what I could to amplify their voices rather than my own.

What makes you enjoy working specifically with youth as much as you do?

How else will I find new music to listen to?

Seriously though, I think literature is a relay race, passing the baton from one generation to the next. I like doing my part to keep that race going, to inspire a few young thinkers the way older teachers and writers inspired me. That’s how progress happens.

Libraries often struggle to adequately serve the teen populations in their area, whether due to lack of funding or personnel who are passionate about working with teens. As someone who used to be a librarian, how do you think libraries can best serve and continue to be relevant to teens?

Listen to teens; include their voices in the process of programming, organizing, and collection building. Keep them involved and value their perspectives as stakeholders. Show them they are valued and they will return the favor.

You have mentioned before that you used to be a reluctant reader. What changed that for you? What do you think can be done to help more young people find their love of reading?

It’s no longer revolutionary to say the key is reading choice. Let readers read what they want and they will find what they want to read. Our job is to create access by building diverse collections that speak to a variety of levels, tastes, and experiences, and to help with the discovery process through book talks, displays, activities, programming, reviews, and encouraging peer to peer recommendations. The right book at the right time can unlock the parts of yourself you didn’t know existed, but you have to access and that is where libraries do vital work.

In light of the debate of whether funding should be cut to the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Arts (something that obviously impacts us a lot), do you have any opinions about humanities-based programing like Teen Reading Lounge, or about the importance of valuing literature and all the humanities as a society?

Obviously, as a producer of books, I’m biased, but I believe these things are essential. There is a reason that art and literature have endured even the darkest times in human history and that brave souls have risked their lives to smuggle books in and out of repressive regimes. Individuals can be destroyed. Ideas endure. Our laws are the form our society takes, but the humanities–our intellectual traditions, our literature, our cultural institutions, those are the content. Those are the things that create meaning we can pass through generations, expanding and refining what we mean when we say ‘We.’ Without the humanities, the fabric of our society starts to unravel and we become mere products of our geography. Art, literature, ideas–and the institutions that make them accessible to all–those are the threads that stitch society together. I shudder to think what would happen if they all unraveled. It’s not easy to stitch together again. But it’s a challenge the humanities are up for if necessary. Come what may, art endures.

![[color – dark bg] PA SHARP FINAL FILES DB 72dpi [color - dark bg] PA SHARP FINAL FILES DB 72dpi](https://pahumanities.org/uploads/files/elementor/thumbs/color-dark-bg-PA-SHARP-FINAL-FILES-DB-72dpi-phgl7aimtfdpzt2rscvl43ksfv3asbbls19lsvuacw.jpg)