By Karen Price

Benjamin Chew was one of the most powerful and wealthy men in Philadelphia in the 1700s, and his legacy includes an estate in the city’s Germantown neighborhood and approximately 230,000 documents related to the family’s lives and business dealings.

It also includes being head of one of the largest slave-holding families in Pennsylvania. Details of the family’s history of enslavement and indentured servitude are included in those many documents, and as research has brought more of that difficult history to light over the last decade they haven’t shied away from sharing it at Cliveden, the former family home.

“As this more in-depth history of enslavement was coming out, we embarked on this project to really overhaul the interpretation here to not only talk about the Chews, but also talk about the servants and the enslaved people that labored for them who we’re still learning more and more about,” said Carolyn Wallace, education director at Cliveden.

Cliveden remained a family home until 1970, when they turned it over to the National Trust for Historic Preservation. It opened as a museum in 1973, and most of the focus was on Chew’s life, the Battle of Germantown, and the home itself as an example of elite architecture and design in the American colonies. Then about 12 or 13 years ago, Wallace said, staff members were researching a plantation property in Delaware and found stories of a slave uprising at the location. The more they learned, leadership knew it was time to overhaul the interpretation at the museum to include stories about the enslaved people and indentured servants who labored at the family’s homes and plantations.

“We got a new interpretive plan and a new core exhibit in our carriage house visitor center that questions what is life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness?” she said. “What does that mean to people who were enslavers? What does that mean to people who were enslaved, and held in bondage, and especially at a site that was a Revolutionary War site? We’re fighting for liberty, but liberty for who?”

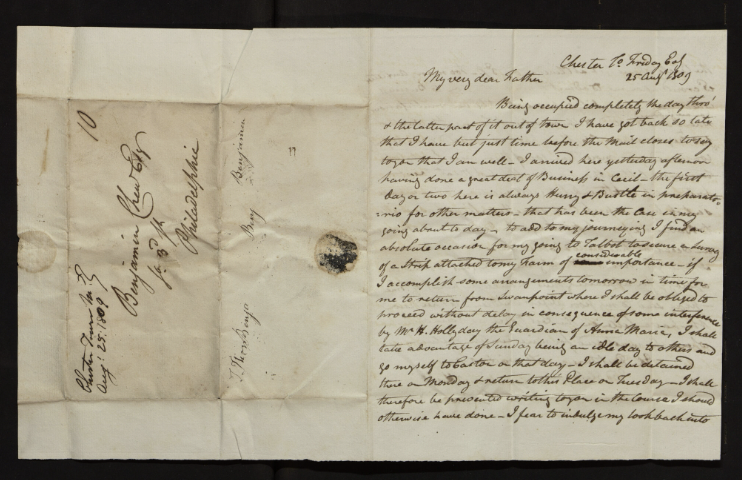

Through grants and other funding, Cliveden has worked with the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, where the documents are held, and the African American Genealogical Group to digitize some of the papers and make them available online. The project is entitled “Illuminating Hidden Lives: Black Stories of the Mid-Atlantic Region,” and one hope of the work, Wallace said, is to find descendants of the people who were bound to the Chew family. A total of 116 documents have been digitized and made available to the public so far. They also gave a presentation entitled Finding Black Families: Stories from the Chew Family Papers in 2022.

Another result of the reinterpretation project is Liberty To Go To See, a play based on research into the family papers and includes the men and women – black, white, enslaved and free – who worked for the family. The title comes from a letter an enslaved man, Joseph, wrote to Benjamin Chew, Jr. asking to go to another plantation to be near his wife. One letter they discovered more recently, Wallace said, was from Benjamin Chew, Jr. to his uncle, who owned a number of plantations along Maryland’s eastern shore. It mentioned Joseph’s request with a disturbing callousness that was all too common.

“He says, ‘I hope this isn’t much trouble for you, but what should we sell him for? What would be a good price?’” Wallace said. “Here’s this paragraph saying, ‘Hi uncle, what’s going on, how’s the weather, how’s the family, how much should we sell this man for, hope all’s well, give love to Uncle John.’ And it’s just so telling about that time period.”

Part of the impetus for changing the stories they tell at Cliveden over a decade ago was recognizing the diversity of the neighborhood and seeking to better serve their immediate neighbors. During the pandemic, they further learned the importance of the five-and-a-half acre property as an asset both educationally and as a much-needed greenspace in Germantown. PA Humanities awarded Cliveden a PA SHARP grant – Sustaining the Humanities through the American Rescue Plan – to help make the space even more inviting to neighbors and making the humanities more accessible. New signage will soon help to spread the word that all are welcome to enjoy the grounds and outdoor exhibits free of charge and shares news of upcoming events, conversations and other activities. Cliveden is also planning to expand its open space offerings and outdoor exhibits.

With ongoing research, Wallace said, they continue to uncover more information about the history of the property and the people who lived and labored there and to adapt their storytelling to reflect that knowledge. Even today, she said, there are people who are surprised to learn that slavery even existed in Philadelphia, particularly among Quaker families.

“So I think for us, it’s about having those conversations and leaving room for all that complicated history and trying to parse that out with folks,” she said. “But most of the people who come here for tours and programs are totally open to that.”

![[color – dark bg] PA SHARP FINAL FILES DB 72dpi [color - dark bg] PA SHARP FINAL FILES DB 72dpi](https://pahumanities.org/uploads/files/elementor/thumbs/color-dark-bg-PA-SHARP-FINAL-FILES-DB-72dpi-phgl7aimtfdpzt2rscvl43ksfv3asbbls19lsvuacw.jpg)